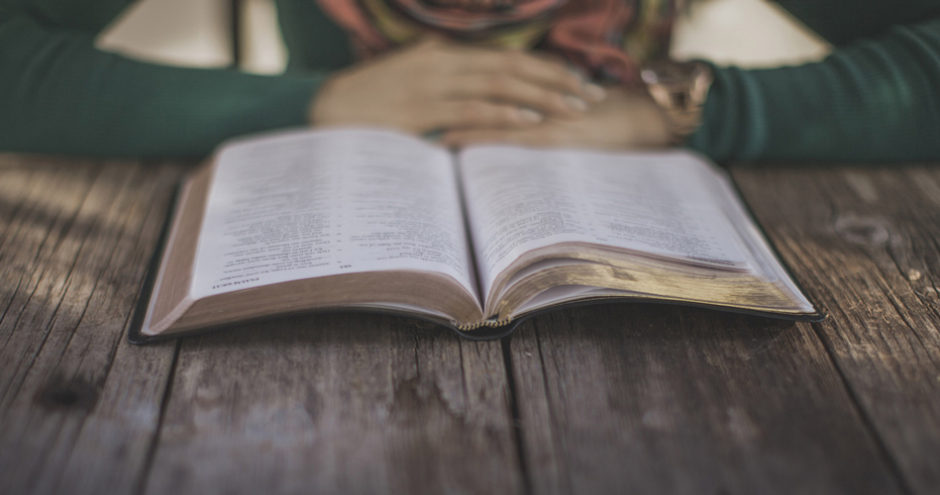

My wife and I are blessed with five amazing children, and our Bible times with them are often hectic, crazy and disordered. Despite such chaos, I desire as a Christian father to unify my family around the things most important to God. Indeed, sitting around our kitchen table memorizing Bible verses and learning the surrounding stories help focus our family on God’s mission to make disciples. It is part of how I let God lead them and shape them. As I walk my children through the opening chapters of the Torah, for example, Noah’s status before God is a key principle. Genesis 6:9, therefore, with its discussion of his righteousness amidst the flood, is one of the first Bible verses that my children memorize.

Noah was a righteous man; he was complete in his generations. It is God with whom Noah walked (Gen 6:9).

This powerful declaration of Noah’s righteousness appears just after the author’s comment in Genesis 6:8 that “Noah found grace in the eyes of the Lord.” Such descriptions of Noah sharply contrast with the surrounding context. Humanity dwells constantly in its own sewage of sin. Specifically, as we read these pages, we see that God’s heart grieves because the hearts of the very men He created are wicked… all the time and in every way:

And the Lord saw that the evil of man was abundant in the land and that all of the inclinations of the thoughts of his heart were only evil all of the day (Gen 6:5).

Moses echoes this same idea towards the end of the flood narrative in Genesis 8:21, forming a frame around much of the story: “And the Lord said in His heart, ‘the inclinations of man’s heart is evil from his youth.’ ” Thus, surrounding the righteousness of Noah and the deliverance he receives are the hearts of men constantly bound up in evil. He is a mere ray of light in a dark world. What can he do? He can obey God and trust God through the flood.

Noah’s deliverance through this judgment to dry land reflects, at least partially, a “new” humanity living in a “new” creation. While man finds a fresh start here, Noah brings his own heart struggles with sin and those of his family into this “new” world. A few verses after the flood, unfortunately, the “newish” creation begins to look a lot like old Noah himself. Noah’s sin prepares the way for his son’s sin and the painful reminder that Noah’s righteousness was not his own. That is, because Noah reflects Adam, Noah’s world also looks like Adam’s world. As Adam sins by eating of the fruit (Gen 3), so Noah sins by drinking of it (Gen 9:20–27). And sin carries on in the hearts of all men … even us.

Most children’s Bibles bypass Noah’s failure. It’s no fun to see your hero fall. However, the fall of Noah is critical to how the biblical author, Moses, wants us to understand Noah… and ourselves. Pride is our enemy and idol. Noah is not the hero. Neither are we. Instead, the author intends us to seek a hero who surpasses Noah: the promised Messiah. Ultimately, Noah’s story stands alongside Abraham’s, Jacob’s and David’s stories (to name a few) to teach us to trust that God and His Messiah is the only Hero.

And, yet, Noah is righteous because he displays that God is righteous through his relationship with Him. More precisely, God’s righteousness is imputed to (grafted uncomfortably onto) Noah by grace through faith. This is the tension for Noah and us: we are not as we will be. We wear a righteousness that runs counter to the affections of our hearts. It is a righteousness of God’s affections that we will share with Him in the end. Our life with God today, therefore, anticipates the perfect life we will have with God after death. Both Noah’s obedience at the story’s beginning and his fall at the story’s end reveal God’s perfection. As such, Noah’s fall defines the nature of Noah’s righteousness: imputed, not of his own. It is not based upon his perfection because it’s not there; it is based on God’s. In this flood story, the judgment of a dying evil world and then the dying righteous man, Noah, becomes the very vehicle to communicate that God creates life out of death. Noah is His messenger. Hopefully, the reader becomes one, too.

But, how should we bring such thoughts of Noah’s righteousness to our children? My younger children see in Noah an obvious contrast between one good guy who does good all of the time and lots of bad guys who rarely know even how to do good. It is, in their minds, not too dissimilar from a “B-Western” from the old Hollywood studio system. Being sinful like their father, they naturally have a low standard for righteousness. My goal, however, is to guide my children to a more faithful interpretation beyond what they know today and what they can see on their own. I hope to reach them where they are and yet prove faithful to the text so that what I teach them will not need to be “unlearned” as they grow in Christ.

As parents, unfortunately, we often find ourselves tempted to reduce Bible teaching into mere moralism: “do’s and don’t’s.” That is, quite often Old Testament stories become vehicles for what we must do and not do rather than as part of a larger story of God’s relationship with man. What we do is very important, but it must not lead us away from depending on Christ and His righteousness. If we teach people a set of mere instructions disconnected from the gospel, we are working against the biblical text. If we work against the biblical text, we are not making disciples of Jesus.

More precisely, moralism’s danger stems from the pride that it may build up in the reader. When we moralize the biblical text, we tend to lower God’s standard for righteousness to mere acceptable behaviors and, in so doing, make God’s righteousness attainable by our obedience. This is wrong and dangerous. It stands as the exact opposite of the biblical author’s intention, and it persuades people that they do not need a savior. While the biblical text aims to show us how far we are from God—even Noah and Moses succumbed to sin, for example—moralism shows us how close we are. This is the problem. Are we a help or a hindrance in passing on the gospel to our children? We must help them to reject seeing the world via the prism of “us and them” with mere good guys and bad guys. They need to humbly compare themselves to those who stumble so that they can see the text and their world as “us and Him.” Again, only Jesus is the Hero.

Such moralizing leads to well-intentioned error and division because it avoids the gospel tension of living in the world while also not being of the world. To remove that tension is to remove the gospel call to make disciples. It is, in other words, to divide one from Christ by separating that one from his call in the Great Commission. Such division can invade any heart via pride and lead to a dangerous tribalism. The irony is that those who misread the biblical text and cast themselves as the “righteous” and the “hero” suffer the greatest cost by limiting where and how and why they walk with God. That is, the ultimate division of mere moralism is a division of the reader from God.

Will we pass on the unity of life with God in Christ when we teach the Scriptures, or will we divide our children from Him by only teaching behaviors that will not stand the test of time nor the final judgment of the day of the Lord? That question is the question of righteousness that divides all men, even a family huddled around the Bible. Will we admit that we are the problem as we sit at the kitchen table together? We must if we want the unity and peace that comes from Jesus Christ.

1 Comment

Good points indeed. I will try to not fall in the pitfalls of do’s and don’t’s in my family devos or in my example and life while keeping the req’t of obedience w/ which w/o no one can enter the Kingdom.